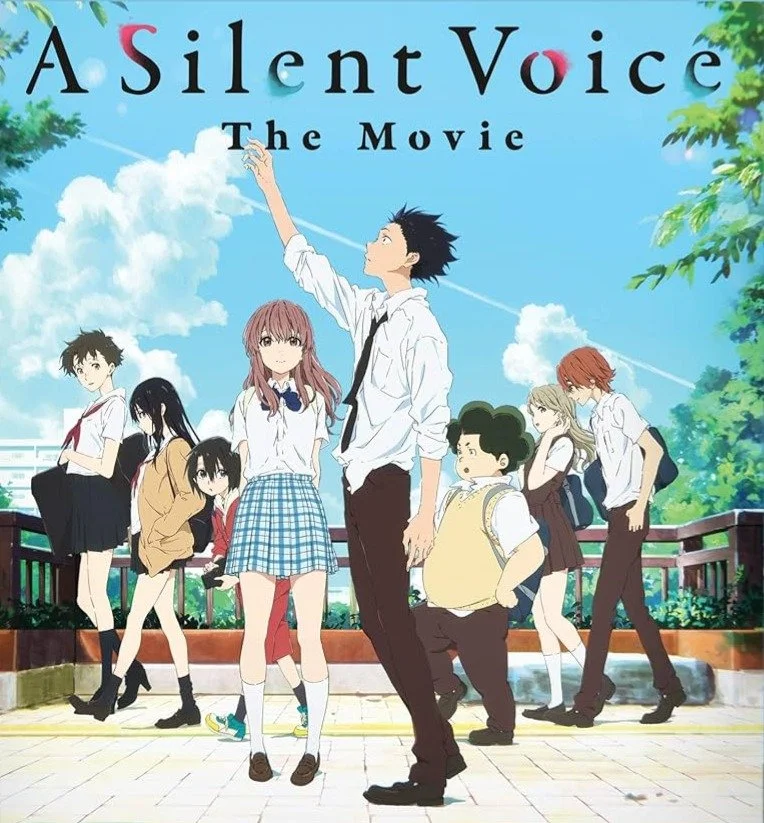

A Silent Voice Review (2016) – A Tender, Devastating, and Necessary Meditation on Harm, Healing, and the Courage to Keep Living!

Some stories arrive gently. Others arrive like a quiet weight on the chest. A Silent Voice is the latter. This week, we potatoes are sitting with A Silent Voice (2016), a film that is soft-spoken, deeply uncomfortable, and profoundly humane. In a world that feels increasingly loud, cruel, and unforgiving, this film does not shout its message. It whispers. And somehow, that whisper lands harder than a scream.

Before we begin, a necessary and gentle heads-up. A Silent Voice explores bullying, ableism, social isolation, self-harm, suicidal ideation, trauma, and long-term guilt. These themes are handled with care and intention, but they may be deeply triggering for some viewers. Please take care of yourselves while watching and while reading. This is a heavy one. It is always okay to step away, pause, or return later.

As always, we will try to avoid major spoilers, but some elements of the story will be discussed. Please read with care.

There’s a lot to unpack with this amazing film, so let’s begin.

The film opens not with hope, but with finality.

We meet Shoya Ishida (Miyu Irino, Robbie Daymond), methodically tying up loose ends. He sells his belongings. He plans his last day. He is not dramatic. He is exhausted. And that quiet exhaustion sets the tone for everything that follows.

Then, the story rewinds.

We are taken back to Shoya as a child, (Ryan Shanahan) loud, impulsive, bored, and cruel in the way children often are when they are not taught empathy. A new student transfers into his elementary school class. “Everyone take your seats. We have a new student that’ll be joining us today.” Her name is Shoko Nishimiya, (Saori Nishimiya, Lexi Marman), “Would you like to introduce yourself?”

She is oddly silent as she looks over the classroom. The class is hanging on the edge of their seats waiting for her to speak… only she doesn’t. She pulls out a notebook from her backpack. She has already written out an introduction to the class, but the class is confused until she reaches the final page of her writing, “I am deaf.”

The class quietly gasps. At first, the class is curious. They use the notebook to communicate and things appear to be innocent enough.

But their curiosity begins to wane. And the class becomes impatient. Then resentful.

Shoya becomes the focal point of that resentment. He mocks Shoko, steals and destroys her hearing aids, isolates her socially, and turns her disability into entertainment. The cruelty escalates quickly, fueled not by malice alone, but by immaturity, boredom, peer reinforcement, and the absence of meaningful adult intervention.

Eventually, the blame lands squarely on Shoya. The teachers scapegoat him. His classmates abandon him. And just like that, the roles reverse. As they often do with bullies. Shoya then becomes the outcast. Things intensify even further and Shoko transfers schools.

We potatoes want to pause here, because A Silent Voice does something incredibly difficult and incredibly important. It refuses to flatten harm into a simple villain narrative. Shoya’s actions are wrong. Full stop. The film never excuses them. But it also refuses to pretend that harm exists in a vacuum.

Wrapping up from here! Years later, we meet Shoya again. He is withdrawn, anxious, isolated, and suffocating under the weight of his guilt and shame. He avoids eye contact so intensely that faces appear crossed out, literally blocked from view. He believes he does not deserve connection. Or forgiveness. Or life.

But fate seems to have other ideas for Shoya, and it brings Shoya and Shoko back together. Shoya takes it as a second chance. A chance for change. “Can we be… friends?”

And this is where the film becomes quietly radical.

Instead of centering redemption as absolution, A Silent Voice centers responsibility and accountability. The film explores the slow, painful aftermath of harm, and how cruelty reshapes the person who commits it as much as the person who endures it. As a child, Shoya participates in bullying Shoko not because he is uniquely cruel, but because cruelty is normalized, encouraged, and ultimately rewarded until it becomes unbearable. When the classroom turns on him, the roles reverse with brutal efficiency. He becomes the isolated one. The target. The problem to be removed so the system can pretend it has been corrected.

But this is not justice. It is displacement. The film makes it clear that bullying is not a series of individual moral failures. It is a destructive social mechanism that teaches children to externalize discomfort and then punishes them when the violence becomes too visible. Shoya internalizes his guilt in the same way Shoko internalizes blame. His self-loathing becomes all consuming. He believes himself to be irredeemable, undeserving of connection, and incapable of repair. It is shame, and shame is corrosive. It isolates. It freezes growth. It convinces people that because they did harm, they are harm.

The swapping of roles does not heal anyone. It simply creates another wounded child. The film challenges the idea that suffering can stand in for atonement. Shoya’s pain does not erase what he did, but it does reveal how cycles of cruelty perpetuate themselves when no one intervenes, no one teaches empathy, and no one models repair. The film asks us to see the full impact and to recognize that bullying does not produce winners, lessons, or closure. It only produces more damage, carried forward into adulthood.

Shoya does not seek Shoko to be forgiven. He seeks her because he cannot continue living without confronting the harm he caused. He learns sign language. He sits with discomfort. He listens more than he speaks. He accepts that forgiveness is not something he is owed, but it takes him some time to get there.

Shoko, for her part, is not portrayed as a saint. She is kind, yes, but she is also deeply traumatized, riddled with self-blame, and convinced that her existence burdens everyone around her. The film shows us how ableism teaches people to internalize harm, to apologize for taking up space, to equate survival with inconvenience.

One of the most devastating elements of A Silent Voice is how thoroughly Shoko internalizes the harm done to her. Years of ableism teach her to believe that her existence is the problem. This struck us potatoes very deeply, as this is something we have struggled with. When you are told constantly that you are the problem, you internalize that narrative. It becomes a part of you, a deep-seated belief that is incredibly difficult to uproot. She apologizes constantly, not because she has done something wrong, but because the world has taught her that she is an inconvenience. She believes, sincerely, that “everything is her fault.” That her deafness causes disruption. That her classmates’ cruelty is a reasonable response to the effort of inclusion.

This broke our hearts, and stung. We resonate a lot with Shoko. We potatoes understand normalizing the cruel behavior of others. Convincing ourselves that we must somehow deserve it in order to make sense of it. To survive it. We want to be clear, cruelty is not normal, nor should it ever be. But we digress.

This is the quiet violence of ableism. It doesn’t just exclude. It convinces disabled people that their needs are burdens, that their pain is disruptive, and that harmony would be restored if they simply took up less space or disappeared entirely. The film makes it painfully clear that Shoko’s suffering is not the result of her disability, but of a system that refuses to meet her halfway. Her classmates’ resentment toward writing notes, repeating instructions, or slowing down is appalling, not understandable.

Accommodation is not a favor. It is not extra. It is the baseline of a just society. When we design spaces with accessibility in mind, everyone benefits. Communication improves. Empathy deepens. Communities become more humane. Shoko’s self-loathing is not a personal failing. It is the predictable outcome of being repeatedly told, implicitly and explicitly, that her existence is inconvenient. Watching her blame herself for the cruelty of others is one of the film’s most harrowing truths, because it mirrors the lived experience of so many people who are taught to apologize for surviving in a world that refuses to adapt.

A Silent Voice lays bare how thoroughly institutions fail the very children they are meant to protect. The classroom is not just a backdrop for cruelty, it is the engine that enables it. Shoko’s bullying is not subtle, nor is it hidden. Teachers witness it. Classmates participate in it. And yet the response is silence, deflection, and eventual scapegoating. When the situation becomes inconvenient, responsibility is not taken. It is redistributed. Shoya is singled out as the sole offender, not because he acted alone, but because isolating one child allows the system to preserve the illusion of order. This is not accountability. It is institutional self-preservation.

The adults in this story repeatedly choose comfort over intervention, control over care. They frame bullying as a children’s problem rather than a cultural one, rather than one that has been taught to them, and in doing so, they abandon both Shoko and Shoya. The harm is allowed to fester because addressing it would require acknowledging ableism, cruelty, and complicity. Silence becomes policy. Inaction becomes routine. And the damage compounds. A Silent Voice refuses to romanticize this failure. It shows how systems that avoid discomfort inevitably produce trauma, how authority without empathy becomes neglect, and how children are left to navigate the wreckage alone. The message is unmistakable. When institutions choose not to act, they are not neutral. They are choosing harm.

This next section is deeply triggering, but central to this film. Please protect yourself, and read cautiously.

As a result of the harm that has been perpetuated on both of our main characters, both suffer from suicidal ideation. A Silent Voice approaches suicide ideation not as melodrama or shock, but as the quiet, grinding result of emotional depletion. Both Shoko and Shoya reach points where living feels less like a choice and more like an unbearable obligation.

The film is careful here. There are no grand speeches about despair, no romantic framing of death. Instead, there is fatigue. A bone deep tiredness that comes from years of carrying shame, guilt, and the belief that one’s existence is problematic. Shoya’s decision to plan his death is framed less as a desire to disappear and more as a desperate attempt to stop hurting others, to finally make amends by removing himself from the equation entirely. Shoko’s ideation, similarly, is rooted in the belief that the world would be lighter without her, that her survival is a burden she inflicts on those around her.

This is what makes the film so heartbreaking. It acknowledges that suicidal thoughts can often emerge not from a wish to die, but from the exhaustion of trying to endure. From feeling like there is no version of yourself that is acceptable, no way to exist without apology. A Silent Voice treats this with the seriousness it deserves, showing how isolation erodes hope slowly, quietly, and convincingly. It does not offer easy solutions or miraculous recoveries. It simply tells the truth. That staying alive, in these moments, is not triumphant. It is labor. And sometimes, the bravest thing a person can do is keep going when they have nothing left except the faint possibility that connection might still be possible.

What makes A Silent Voice feel so painfully relevant today is how clearly it mirrors the exhaustion of the world we are currently living in. We are watching these characters pushed to their limits by shame, isolation, and the constant pressure to perform worthiness, and it feels familiar because our world does the same thing to us. They take our time, our energy, our creativity, our mental and physical health, and our relationships, and then demand more. We are expected to sacrifice our bodies and minds for labor that barely sustains us, to be grateful for wages that do not cover survival, to apologize for burnout while systems profit from our depletion.

And when we inevitably collapse under that weight, we are told it is our fault. That we did not try hard enough. That we were not resilient enough. That we failed ourselves. This narrative is extremely dangerous and not at all true. It shows what happens when people internalize blame for harm that was never theirs to carry, when survival becomes synonymous with endurance, and rest is treated like weakness. The world is getting louder, harsher, more punishing, and the film’s quiet devastation reflects that truth. We are not broken for being tired. We are tired because we are being drained. In every way possible, by a system and institutions that give nothing back. And naming that reality, refusing to accept exploitation as inevitability, is not cynicism. It is clarity.

What A Silent Voice ultimately offers is not a promise that everything will be fixed, but the insistence that connection itself is an act of resistance. In a world that isolates us, shames us, and convinces us we are only valuable when we are productive or pleasant, choosing to reach out, to care, to listen, to connect, becomes radical.

The film rejects the fantasy that harm can be erased or that survival must look triumphant. Instead, it argues that choosing to live, choosing to keep showing up even when the shame is loud and the future feels unbearable, is enough. Redemption is not tidy. And love, whether platonic, romantic, or communal, is not a cure so much as it is a lifeline, and sometimes the most courageous thing a person can do is simply stay in a world that has taught them they do not belong; and then, slowly, painfully, build connection anyway.

A Silent Voice arrives not with a speech, but with sound. For much of the film, Shoya moves through the world with the people around him muted, their faces crossed out, and their voices distant or absent altogether. This isn’t a stylistic gimmick, it’s a visual and auditory manifestation of depression, shame, and dissociation. When you are consumed by self-loathing, the world doesn’t feel accessible. People become threats. Noise becomes unbearable. Connection feels impossible. So when Shoya finally looks up and the X’s fall away, when the crowd noise rushes back in all at once, it is overwhelming in the most human way.

It isn’t victorious. It’s disorienting. It’s loud. It’s emotional. And it’s real. The film understands that healing does not arrive gently. Reentering the world after isolation can feel like being hit by a wave. But it also understands that this sensory flood is a sign of life returning. Shoya isn’t suddenly healed. He hasn’t been absolved. But he is present. He is hearing others again. He is allowing himself to exist among people, and that alone is monumental.

The film does not offer the comfort of closure. Shoya and Shoko do not arrive at neat resolutions or healed selves. Their pain does not disappear. Their work is not finished. Instead, the film offers something far more fragile and far more necessary: hope.

Hope is what allows them to begin seeing the world again, not as something closed off and hostile, but as something vibrant, messy, and still capable of beauty. Hope keeps them fighting, surviving, and pushing forward even when the weight of the past remains. And that is precisely why it matters. Healing here is not a destination. It is a practice. And hope is what we need most right now.

Hope that we can make things better. That we can take accountability even when it is painful. That we can repair harm rather than bury it. That we can build a world rooted in connection, care, and responsibility rather than silence and cruelty. A world that reflects the hard, fragile beauty of Shoya and Shoko’s journey.

This movie recognizes something vital that our society tries desperately to deny: that healing is not a distraction from “real work.” It is the work. It may take time. It may be nonlinear. It may never feel complete. But it is the only labor that gives our lives meaning. And choosing it, again and again, is an act of resistance.

A Silent Voice resists easy answers about what heals us, and instead looks closely at the people around its characters, flawed, hurting, and searching just like them. The supporting cast further reinforces the film’s themes. Friends who harm each other while trying to belong. Teenagers who weaponize denial to avoid guilt. Adults who fail repeatedly and quietly. No one emerges untouched. No one is entirely innocent.

At the same time, the film insists that accountability and compassion are not opposites. You can hold someone responsible and still believe they are capable of change. You can acknowledge harm without erasing the humanity of the person who caused it. That is a deeply uncomfortable truth in a culture that prefers punishment over repair.

Crucially, though, A Silent Voice never confuses accountability with entitlement. Forgiveness is not mandatory. It is not a prerequisite for healing. Shoko does not exist to heal Shoya, nor is it her responsibility to absolve him. Her pain is not a lesson. Her survival is not a reward. The film grants her full autonomy, even when that autonomy includes anger, fear, and distance. Her feelings are valid, and she does not owe Shoya anything.

That same care carries through every technical choice the film makes. Visually, A Silent Voice is absolutely stunning. Kyoto Animation’s work is tender and precise. Light reflects off water. Cherry blossoms fall and rot. Silence is treated as a character, not an absence. The sound design, especially in moments centered on Shoko’s perspective, is profoundly effective. We are not just told what silence feels like. We experience it.

And the music. Gentle. Melancholic. Human. It does not manipulate emotion. It accompanies it. The writing is poignant, thought-provoking, and absolutely superb. It is grounding even as you are falling apart.

We potatoes love this film. But, it is such a dark time, and people are looking for comfort. So, why this film? Well, with everything happening this January, this film feels especially poignant, and important to discuss. The world is heavy. People are exhausted. Many of us are carrying shame, regret, grief, and the quiet question of whether we are allowed to keep going after we have failed. Whether we are worthy of moving forward when so many horrific things have happened, and continue to.

We potatoes feel that A Silent Voice answers that question gently and meaningfully. Yes. But not without work. Not without listening. Not without accountability. Not without care. Not without presence. Not without honesty. We are worth the work as uncomfortable as it may be. This is the work worth doing, and the rewards far exceed money.

So is A Silent Voice an easy watch? No. Is it perfect? No. Is it necessary? Absolutely. Is it beautiful? YES. Do we highly recommend it? YES. We are not at all embarrassed to say that we cried a lot while watching this movie. This is a film that hit us hard, but is so worth it. It asks us to be present with the unease. To face it. To resist the urge for tidy resolutions. To understand that healing is not about erasing the past, but learning how to live honestly alongside it.

We potatoes deeply believe that stories like this matter. Especially now. Especially when cruelty is being normalized and empathy feels radical. This film does not offer escape. It offers reflection. And that is honestly the best part about art, and the most restorative thing art can do.

So, if you decide to watch A Silent Voice, do so gently. Watch with breaks. Watch with water nearby. Take your sips mindfully. Watch knowing that it is okay to feel shaken, to feel sad, to grieve and to still have hope.

Cheers to Shoko for surviving in a world that keeps asking her to apologize for existing. Cheers to Shoya for choosing to stay, to listen, and to do better without demanding absolution. Cheers to stories that trust us with complexity. And most importantly, cheers to you. Thank you for being here with us.

Now, we potatoes invite you to join us in sitting with this film. Find somewhere quiet, breathe deeply, and remember that even the smallest acts of care matter. To remember that you matter and you are enough.

We’re glad you’re here.

We give this movie 5 out of 5 Koi Pond Cocktails!

The "A Silent Voice" Drinking Game

Take a sip anytime:

1. Anyone uses sign language

2. Shoko is kind and/or resilient

3. Shoya shows growth and/or kindness

4. Shoya rides his bike

5. Nagatsuka makes you laugh

6. Yuzuru uses her camera

7. Shoko and/or Shoya feed koi fish

8. Koi fish are on screen

9. There’s a flashback

10. There’s an X on screen

11. An X falls off someone’s face

What did you think? Did you like the movie? Did you hate it? What movies should we watch? Any and all thoughts are welcome! Let us know in the comments!

Do you like this drinking game? Are there rules missing? Is the game too intense? Are there movies that you think we should make a drinking game for? Let us know and always remember to be safe and drink responsibly! (Drinks can be water, soda, anything nonalcoholic, etc. Please be safe, have fun and take care of you!)